I recently had an opportunity to visit the magnificent Zeitz MOCAA. I was completely blown away by the artistic excellence captured in both the architecture and the art of the Zeitz museum.

I was also very privileged to sit down with Mark Coetzee, chief curator at Zeitz MOCAA, for a quick lunch to talk about the significance of this museum in Cape Town. The conversation was very insightful, and I feel honoured to share this information.

Significance

The Zeitz museum has set out to promote innovative artists and designers in Africa who have not been recognised, globally, at the level they should have been. Being located in Cape Town, the museum signifies a political, economic, and cultural investment.

The art world has been decolonized for the past 20 to 30 years; therefore, this museum has a very strong commitment to showing that Africa’s voice matters. The art displayed in the Zeitz museum is made by Africans, and it is accessible to all Africans – which helps to reinforce identity and give a voice to our history.

In the past, students studying art history only learned about artists and art from Europe and elsewhere; there was nothing included in the curriculum about art originating in Africa. However, in order to get a holistic concept of art, there has to be something included about Africa. That is what this museum does – it does not want to decolonize the text already written, but rather wants to write a new text.

History

The museum originated as a result of a whole set of circumstances and choices. The Victoria & Alfred Waterfront (V&A) belonged to TransNet (a freight Transport Company), and was used as a working harbour. As the need for transport changed and ships became more and more containerized, the small V&A harbours became useless. The Schoeman docks, a big harbour close by, was then built in the 60s. The construction of this harbour caused all of the buildings in the Waterfront to be transformed into a harbour front where people could live, work, and play.

Historically, the V&A Waterfront is very important.

- Located there is the building from which Nelson Mandela was taken to Robben Island

- The Craft Market, where every immigrant who came to South Africa was processed through, is also located there

- It contains the old jails

- The old fortress is there

Therefore, this entire property contains so much of South Africa’s history.

Every part of the harbour was abandoned, including the site where the museum is now situated. Then, in 1921, it was declared a national monument and could not be altered at all. The Waterfront could not develop that part of the land because of the ugly building in the centre of it all.

The Waterfront then decided to meet up with an architect, Thomas Heatherwick, to consider future possibilities for the building. Discussions later proposed the idea of recreating that specific space into a museum. Possibilities of a ship museum, a design museum, and many others were discussed but never seemed to get off the ground.

After all of these discussions, the Waterfront started looking for a partner to help them recreate the space into something significant.

At the time, Mark Coetzee was working at Marietta museum where he met Jörgen Zeits – the then CEO of Puma. Discussion revolved around Coetzee’s future, and he started sharing his dream of wanting to build a contemporary art museum on his home continent of Africa.

After hearing Coetzee’s heart, Zeitz suggested that they work together on a collection of art, buy a building, and create a public space for people to come together and experience art.

While the V&A Waterfront was trying to find a partner to create a public art space, Coetzee and Zeitz were working on a new project – unbeknownst to each other.

The owners of the Waterfront knew about Coetzee and all of his accomplishments and experience, so decided to contact him and speak with him about possibilities for this specific space. During this conversation, Coetzee was able to connect them with Zeitz. Two weeks later, they all came together and decided to make the museum work. After the span of three years, everything was set up.

To the public eye, it seems like it all happened really quickly; however, both parties had been working individually on this initiative for five or six years before they all met.

After their meeting, all the specifications of the museum’s layout were given to Thomas Heatherwick, who then came up with the complete design of the museum.

Architecture

There are typically many architects who propose different pitches about the design of a specific building, but Thomas Heatherwick came up with such a brilliant idea for the new museum that the organisers did not go through the process of finding someone else.

He connected the nine old silos, the bottom half of the elevator building, and the entire dust house with glass windows on the outside. Because it was a national monument, no changes could be made to the outside of the building. Therefore, all the renovations to the museum had to be done on the inside.

To create authenticity within the museum, Heatherwick asked the organizers to send him a piece of maze to which he could accordingly design the inside of the new museum. He laser cut the design of the mealie and cut it into the inside of the building. Now when you enter the building, it is not just an oval shape, but the actual shape of a mealie. As a result, the atrium of the museum becomes the public’s base.

Before the reconstruction of the museum, no one had walked in it since 1921. The basement area was accessible, but nothing else. Because of this, the builders and designers had to crawl through the tunnels and look up through the tubes to see how they could go about the task. When the process of cutting the tubes started, the designers could not see what they were doing, so everyone had to start cutting in a different tube. Hoping that the tubes would meet, the designers used GPS coordinates to plot out different spots in the tubes of concrete and, through careful communication, started cutting from both sides.

Fortunately, the tubes were successfully connected. To say the least, the site that you encounter when first entering the museum is truly a piece of art in its own right.

Artists

There are two exhibitions running at the same time in the museum:

- Work that the museum owns

- Work that the museum gets from elsewhere

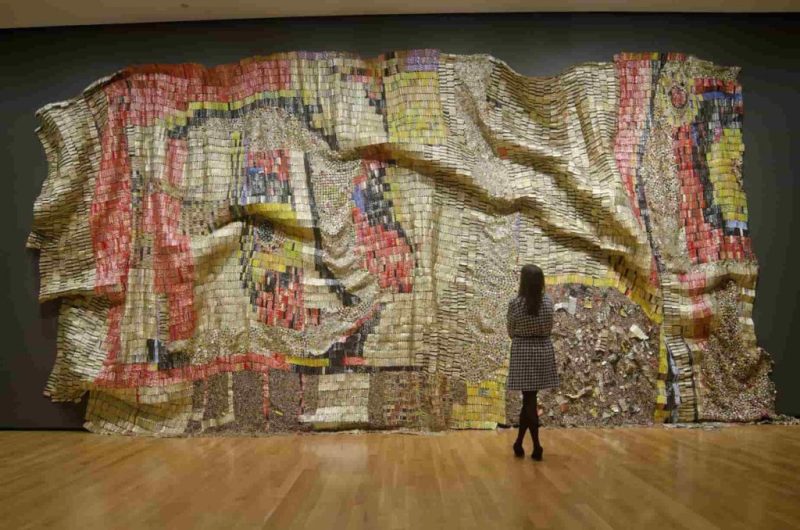

Work that is owned and collected by the museum only focuses on art created by Africa and the diaspora – African-American, Afro-Brazilian, and Afro-Caribbean. The museum shows anything and everything in an attempt to preserve the work from Africa. However, they also bring in work from elsewhere so that local artists can be exposed to a variety of creative interpretations.

The main prerequisite for artists to exhibit in the museum is that they have to be from Africa and the diaspora, and the art exhibited has to be from the 21st century. When deciding on which artists should be displayed in the museum, there is a selection committee of 21 people and an accusation committee of 11 people. These committees look at and consider different artists, then vote on which exhibitions should be displayed.

The museum is representative of what is happening in the public arena; it is diverse and displays good quality, so it has to look for the best work. Finding good work seems like an easy task, but opinions of what is ‘the best’ varies from person to person. These differing opinions can complicate the whole process.

Whatever struggles the committee goes through, at the end of the day, they strive to be relevant to the surrounding society. Art that is the best today is not the best tomorrow.

Special Displays

When setting up the displays, the museum looks at what artists are already doing and allows them to educate, not only curators but society at large. When researching art pieces to display at the museum, two very prominent themes surfaced:

- The Dalai Lama

- The Self-Portrait

The Dalai Lama

White people’s art traditionally lands in art museums, while black people’s art lands in natural history museums. When looking for artworks, the museum thought that no artist will work with the Dalai Lama; however, they found that there were many artists who took the Dalai Lama and just turned it on its head. For example, black people used the “N” word, while gay people used the term “moffie”.

You can get away with this when it is you using otherwise inappropriate terminology. The crudity of it is disempowered when you turn it upside down, and that is what a lot of artists were starting to do.

Artists were taking the Dalai Lama and completely disempowering it by using it in a sarcastic, playful way.

The Self-portrait

It has been incredibly interesting to see the way different artists have dealt with the self-portrait. They use the image of themselves over and over again and add in technology, or other mediums, to represent themselves differently in their work.

In a country where the government has previously decided the fate of art – which race we belong to, what we can say and not say – the idea of having the freedom to say (not only that we have a voice), but also to occupy the physical space of expression, has been very significant and a fascinating representation in the museum.

How has the museum been received?

The museum was announced three and a half years ago, and people were very happy and excited to hear about the prospect. When the museum’s doors opened on the 22nd of September 2017, between 5 and 6 thousand people arrived every single day. In fact, people continue to keep coming back. There has been an overwhelming amount of positivity about the museum. The architecture is amazing, and people love the art and the fact that it is in our own city.

In the past, cities had been built around the central structures of cathedrals. The cathedral distinguished a town from a city. However, in our present day, museums seem to have taken up that role.

Having placed this unique museum in the city of Cape Town, also speaks to the fact that “who we are” matters. South Africans have a huge sense of pride, and by having a museum based in our own country, we are now able to boast about the fact that we can display who we are on an international platform. In essence, artists present who we are. So if they are presenting who we are, on home soil in what is becoming an internationally renowned museum, who we are surely matters.

Another great positive point about the museum is that it is extremely accessible to South Africans who would otherwise never have been able to travel overseas to visit museums. In addition, admission is also very affordable with special deals for locals.

Overall, the museum has been received by the public with a very positive and excited attitude.

Location

When the idea of the museum originated, Coetzee and Zeitz started looking for the right space all across Africa. They planned on first buying a building, then creating a public space from there.

The V&A Waterfront was ideal for this because they receive approximately 24 million visitors per year. Of these:

- 60% are Capetonians

- 30% are from the rest of South Africa and Africa

- Only 10% are international tourists

The Cape Town area, in general, is still pretty divided because of the mountains and ocean. People are not really integrated, and this transfers onto the V&A Waterfront. Even though the V&A might not be an integrated space, it definitely is a shared public space.

Another wonderful thing about the Zeitz museum is that it is located very close to downtown Cape Town. The museum’s principle of “access to all” has truly been rolled out, both in transportation and admissions.

The overall modern, harsh, industrial look of the building also works great with contemporary art. The building itself, plus a very generous donation for renovations, was given to the organisers of the museum by the V&A Waterfront. This building worked perfectly because other available buildings would have taken about ten years to create the proper space, and no one could wait that long!

Future

When asked how the success of the museum would be marked, the curator responded with his main mission:

We want to be a museum in Africa, for Africa, by Africans. We hope that it will always be a place of diversity in nationality, race, gender orientation, and religion.

~Mark Coetzee

It is obvious that the museum also represents this with their staff. There are about 52% men, 48% women, and a very good representation of all races employed.

It is also evident that this is a non-prescriptive institution. In the past, during Apartheid, artists would either be a status quo artist: painting landscapes or still lives which portrayed that the land was completely empty and up for grabs. Or artists during the Apartheid era were part of the opposing political party, the ANC (African National Congress) cultural desk. This meant that a lot of resistance and anti-apartheid art was created. With these being the only two choices, artists were forced to choose a side.

Consequently, the organisers of the museum realised that they could not tell artists what to do, because that would just be propaganda. The hope for the future is that the Zeitz museum will be an institution that is unpredictable and non-prescriptive. The museum chooses to not tell artists what is wrong, right, good, or bad art, but to just let them create what they want. The Zeitz museum truly creates a platform where different conversations can take place.

For most museums, the success of a museum is measured mainly by the number of people that pass through. Some have 10 – 15 thousand visitors a year, but the Zeitz museum achieved that goal within the first week and a half of opening. The Zeitz has undoubtedly proved itself as a world-class museum with exhibitions of extraordinary standard, and the numbers prove this.

Identity is completely fluid. That’s the nature of what it is. Through life experiences we change.

That is why the Zeitz museum strives to respond to what is happening in the public, and not only stick to strict regulations of what might be ‘expected’. Our identities are forever changing, and art has to remain relevant to that phenomenon.